In which we meet Captain James R. Kirk and the valiant crew of the Enterprise as they venture beyond the great barrier at the edge of the galaxy.

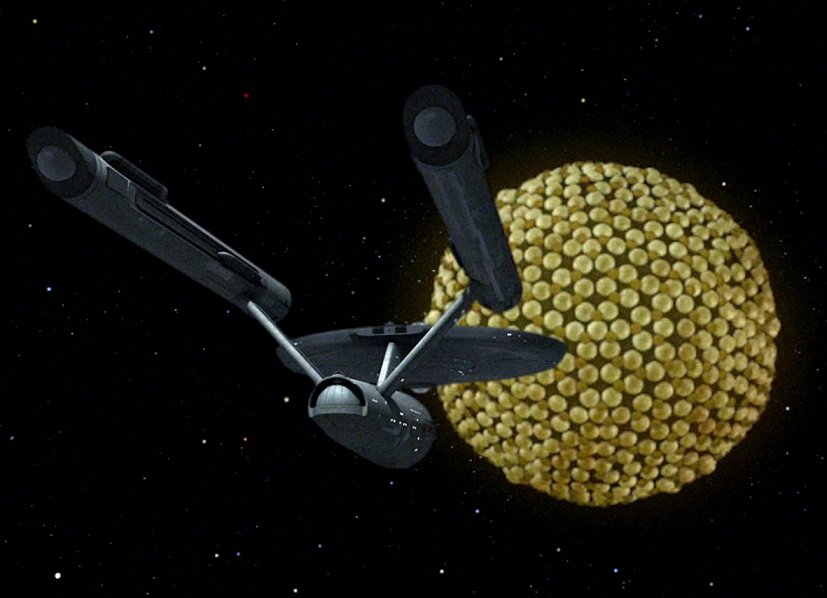

The single most striking thing about this, the very first episode starring Captain Kirk, the second pilot film for the series, the episode meant to sell this whole venture as a series, is the way it begins: a chess game between Kirk and his alien science officer. No grandiose introductions to the vessel and its mission. No tedious assemblage of a team and shots of a captain getting his first command. No origin story at all. We’re simply thrust right into the action. This is the story of a captain and his crew and we learn everything we need to know about the ship, its mission and the dynamics between crew members by watching the story unfold. Even the opening title sequence lacks the traditional “These are the voyages” narration. We’re dropped into the future, onto a starship exploring the outer fringes of the galaxy, with almost no explanations for anything. Technology is taken for granted. When Kirk orders the Valiant’s stray recorder be brought on board, we cut to the transporter room and watch the machine appear on the platform. There’s no expository dialogue about dematerialization, no explanation given or necessary. We see it happen, we’re shown, not told, in the way the best stories are always handled. Just do it and trust the audience to figure it out.

Another striking element is the story itself and the overarching themes brought up. This is man versus god, or, more specifically, a man with godlike powers. It’s a theme Roddenberry will bludgeon us with over the decades to come, including the TNG pilot (where we spend a ton of time putting the crew together and learning their backstories before tangling with a being gifted with godlike powers). Roddenberry consistently presents humanity, raw and vicious as it can sometimes be, as ultimately preferable over omniscient hyperadvanced species. Maybe, somewhat ironically, he’s illustrating a verse from the Bible (King James version): For in much wisdom is much grief: and he that increaseth knowledge increaseth sorrow. We also get arguments about the merits of compassion and emotion, concluding with Kirk’s comment that there may be “hope” for Spock after all. Emotion, compassion, are vital elements, not just of a commander, but of a human being. Gary Mitchell’s use of superpowers robbed him of the capacity to identify with ordinary people, stripped him of his very humanity. As we learn over and over again in science fiction, with great power comes great responsibility.

pilot (where we spend a ton of time putting the crew together and learning their backstories before tangling with a being gifted with godlike powers). Roddenberry consistently presents humanity, raw and vicious as it can sometimes be, as ultimately preferable over omniscient hyperadvanced species. Maybe, somewhat ironically, he’s illustrating a verse from the Bible (King James version): For in much wisdom is much grief: and he that increaseth knowledge increaseth sorrow. We also get arguments about the merits of compassion and emotion, concluding with Kirk’s comment that there may be “hope” for Spock after all. Emotion, compassion, are vital elements, not just of a commander, but of a human being. Gary Mitchell’s use of superpowers robbed him of the capacity to identify with ordinary people, stripped him of his very humanity. As we learn over and over again in science fiction, with great power comes great responsibility.

Other elements that popped out at me, particularly with the benefit of seeing what happens in the future, are little things. Spock’s quick conclusion that Mitchell should be dumped off on a nearby planet (eerily reminiscent of young Spock’s actions in the latest Trek movie). The mention of the blonde lab tech Kirk almost married (which immediately brings to mind Carol Marcus). The ubiquitous Eddie Paskey.

Stylistically, the show is still finding its ground. The uniforms are noticeably different, in color, collar, and decoration. The bridge retains elements of the almost primitive look it had in the first pilot, The Cage. The phaser props seem too Flash Gordon-y, the communicator needlessly chunky, highlighting what a terrific job the production team did with redesigning things when the series fully launched itself. Also missing is the emotional core that McCoy provided. Dr. Piper is just another member of the staff, not the trusted advisor and deeply humanistic conscience Kirk comes to rely on. Spock is almost himself here, but still barking orders and acting a lot more, well, emotional. But Kirk is pretty much Kirk. Except, of course, that his middle initial is wrong on his tombstone. Makes me wonder if that got digitally changed in the “remastered” version.

Alexander Courage’s music here is mostly too melodramatic, but there are a few classic moments, especially the slow build when Mitchell starts reading faster and faster. His music here also demonstrates how much Fred Steiner contributed to the feel of the show starting with the very next episode, The Corbomite Maneuver. Sure, Courage wrote that bongo-inflected main theme and both Gerald Fried and Sol Kaplan wrote some of the most iconic moments for episodes much later, but Steiner is the true architect of the Star Trek sound and it’s noticeably absent here.

After the “too cerebral” pilot, Roddenberry delivered an episode that still manages to give its characters a lot of thoughtful dialogue while also upping the action quotient. In an earlier review of the latest Star Trek movie, a commenter pooh-pooh’ed my opinion because the original Trek was “thoughtful, provocative, while this was eye-candy.” This episode, Where No Man Has Gone Before, proves to be an excellent example of that very point. This is science fiction filled with ideas while at the same time giving us slam bang action. I loved the new Trek movie because it was tons of fun to watch, a rollicking good time no doubt enriched merely due to its heritage. I loved Where No Man Has Gone Before because it was a great story that made me want to find out more about these characters, this ship and this universe. And, thankfully, we’ve been given more for some 45 years and counting.